Jo Rundle

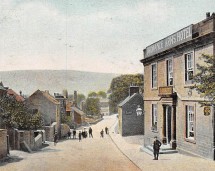

Old Totley

Part One

It is a matter of conjecture as to what was 'Old Totley', and how far back one has to go, for every decade has some of the old and some of the new. In this case I am assuming that the person who wishes to know about 'Old Totley' means the life-time of the oldest members of today's society, the early 20C.so this is where I shall begin.

Life in the village was slow and comparatively quiet during the first decade of 1900, The Boar War was over, although there were still those with memories who talked about it, and sang the songs of the time. The dirt roads were surfaced with limestone chippings, not easy for the horses who pulled the Stage Coach every morning from Sheffield to the 'Changing-post' at The Cross Scythes Hotel farm on its way to Bakewell. After the steep climb from Totley Rise an overnight stay in the 'Baiting-shed' (Now demolished for new housing) must have been very welcome to the horses, to be ready for the return journey to Sheffield next day about 4.30pm. In 1912, the Parish Council asked Norton District Council if they would surface the road from Totley-Rise to Totley Village with tar macadam as they had already done up to Totley Rise, and the Council agreed, but, due to the outbreak of the first World War this was delayed until 1917 The Council members were obviously very proud of the new road for they instructed the Clerk to the Council to send a message to the Scavenger to ask him not to empty the ashpits after the roads had been swept on Saturday by the District Council. This obviously referred to Grange Terrace and those houses on the new road as the District Council were responsible only for the main roads, the Parish Council being responsible for those in the village.

The road sweeper was Joe Marshall, recently moved from Shrewsbury Terrace to the cottage at the end of Hall Lane, whose job it was to sweep Hillfoot Rd/Town Street, Penny Lane, The Bents, and Lane- head Road, every day, including collecting all the horse droppings, which almost certainly ended up on the front garden of his cottage. About 1923 Hall Lane, and the stretch of Hillfoot Road through the village, were surfaced with tar- macadam, but only the centre of the main road up to Lane Head was given the same treatment, leaving about 6ft. of limestone on each side. The footpath was still bare earth with chippings, except for a 12" border of grass that strengthened the edge against fouling of the surface drains.

The children at Lanehead were very happy, especially the boys, for now they had somewhere to play with their 'Whips and tops' on Shrove Tuesday, and iron rims made by Mr Bradshaw the blacksmith in his forge in the Chemical Yard. Using the hook specially designed to control the rim they travelled down the new road at a mighty speed. Even the girls created less dust as they dashed around with 'Shuttle-cock and battleboard'. This part of the main road was not fully surfaced until about 1924 along with the rest of Hillfoot Road, Penny Lane, the Bents and Lane-head Road. My Brother (2 years older than myself) and I remember seeing barrels of tar being deposited at intervals on the edge of the main road, followed a few days later by the appearance of a Steam- roller and other mysterious contraptions.

One morning a gang of men appeared and all the children at Lane-head watched as two men tipped one of the barrels of tar into a large container on top of a fire-box on wheels, and were fascinated to see the tar appear through the holes in a long perforated pipe as it was sprayed onto the surface of the road. A gang of men followed as they spread limestone chippings thickly over the tar and using long-handled rakes spread them over the surface before they were rolled in by the steamroller following behind. Very soon after this the whole road was surfaced as far as Baslow.

There was only one car in the village, a 'Crossley' owned by Mr. Milner of Totley Hall, and, although Totley Tunnel had been opened in 1993, travel out of the village was by Stage Coach until the arrival of the first Horse-bus in 1911. Goods were brought into and sent out of the village on Jimmy Larder's dray to and from Dore Station, and it was always possible to beg a lift from him if, and when necessary. There was, however, much horse-drawn traffic for milk-floats, and farm carts passed daily on their way to Sheffield carrying swedes, clover, and grain to the city farms, returning with loads of manure, otherwise difficult to dispose of, and welcome to the country farmers. A letter to the Parish Council on 16th October 1912 from John Wood Headmaster of the Church of England School requesting, 'that a Motor 'School sign' be fixed on the main highway just above Post Office drawing attention of the drivers of motor cars to the proximity of the school', suggests that there was some motor traffic through the village at the time, although most country folk know that a galloping horse's hoofs can be more dangerous than the slow moving motor cars of that time.

Soon after the road was fully surfaced, in 1924, a small 'bus belonging to 'Batley's Charabancs' of Sheffield, carrying one or two passengers, passed once a day on it's way to and from Baslow, soon to be taken over by the first Sheffield Corporation bus to Baslow and Bakewell at 10 o’clock in the morning, passing the cottages on it's return journey about 4.30 in the afternoon. A lone waggonette passed Lane Head occasionally, believed to be that belonging to an elderly couple Mr. and Mrs Hawes who lived in a cottage in the lane leading from Totley Rise to the Chemical Yard, and soon there were one or two cars each day, but they could be heard well before their appearance around the comer at the top of Lane Head Road, and we had plenty of time to pick up our tops and shuttle-cocks and move out of the way.

Boys in the village made trolleys out of orange and apple boxes begged from Mr. King the greengrocer at Green Oak, or from Mr. Evans at the shop in Hillfoot Road, and my brothers were no exception. Elijah, the eldest, made a trolley with such a box, and a set of pram wheels, perhaps donated by my Mother or kind neighbour or, more probably found on the Brickyard tip. Trying it out for the first time on this lovely new road he was just picking up speed when the Bakewell 'bus came around the comer above Lane Head and followed ever more closely behind him until, on reaching the War Memorial and the last stretch into the village, there was no escape but to dive for the gutter and hope for the best. Luckily both brother and trolley survived, and the bus-driver had the last laugh!

Part Two

There was no electricity, nor street lighting, at Lane Head until 1929, although there may have been some lighting on Summer Lane and in the immediate village. The only outside light was a single bulb attached to Kirby's barn, where it was the custom, even in those days, for the male population to congregate for their favourite pastime of gossip and teasing the passers-by, usually girls. If a light were needed, it might be a carriage lamp, a candle in a jam-jar or candlestick or, in my family, a pit lamp, the use of which sometimes caused great interest, or cynical humour. It happened one night when my Brother Elijah found himself on a journey to the 'Top shop' carrying my Father's safety lamp to provide illumination. When he reached the corner of Hall lane, there was the usual congregation of males enjoying the gossip of the day and ripe for a teasing session should one arise. This time it was my brother who hit the firing line, when one bright spark started teasing and attempting to blow out the lamp; no matter how hard he blew and poked, the offending light refused to disappear until the blower was in danger of losing his reason and stamping on the offending lamp. Luckily, the rest of the men realised that the fun had reached the point when interference was called for, and my brother made a very rapid dash to the shop.

When eventually electricity reached Lane Head it was the opening into another world, to say goodbye to the paraffin lamp, to sit on the sofa to read instead of all having to sit round the table reading in lamplight; for my Mum to have a little electric cooker instead of always relying on the fire, a simple switch to light my way up the stairs to bed instead of the candlestick and the fear of someone catching my last leg as I ran upstairs to bed and knelt in trepidation of the same spirit when I knelt beside my bed rapidly gabbling a prayer, but the greatest joy for my brothers and myself was, after listening on the 'Cat's Whisker' that Mr. Turner my Father's bowling-club friend had loaned, was our own dome-shaped wireless that made us rush home from work every evening to crowd around and listen to Henry Hall and his dance orchestra every evening at 6 .15 to 6.30pm a quarter of an hour of sheer bliss, that brought grunts and groans from my Father in protest at this new-fangled music that compared very unfavourably with Excelsior, The Old Organist, Nellie Dean, or even Kathleen Mavourneen. And we had a streetlight! under the tree at the Memorial. No longer was the walk home in the dark to be feared, nor even in the moonlight, as when I was 12yrs.old and returning home from Chapel, when, just before reaching the Memorial I saw a huge white shape rise from the gulley just below the cottages at Lane Head that shone in the moonlight and floated slowly, very slowly down the centre of the road. Mesmerised I walked in trepidation as it floated nearer and nearer twisting and turning gently in the breeze. Should I dash for the Memorial and hide?, or turn round and run? 1 stopped, staring, as it floated nearer and nearer now growing just a little frightened. It reached the Memorial and, just as I was about to panic and run for my life it floated gently to the ground and I realised with almost hysterical relief that it was a whole sheet of newspaper that had obviously been lifted out of the ravine by the breeze and carried so gently until the breeze was diverted by the trees and the Cross. I was very happy to see the new street lamp at the Memorial a year later, probably more welcome than Henry Hall.

Totley was well served with 'Pubs', all with their distinct clientele The Cross Scythes Hotel and farm, until the first horse- bus arrived in 1911, was the Changing-post for the stagecoach horses that were fed and kept overnight in the Bating-shed (Recently demolished for house building). It had changed hands many times since my Great- Great- Grandfather Thomas Fisher left there for Hallfield farm in 1851, and was popular with Stagecoach travellers and later the passengers who ventured into the country in the first Horse-bus in 1911. There were others who enjoyed its somewhat more superior appearance and possibly more sophisticated customer. The 'Fleur de Lys' was the 'Local' for most village men and farmers, although a few years earlier the Ale House in Town Street, (Later Walter Evan's shop, until he built and moved into the shop at the top of main Avenue) had been handy for 'Take-a-ways', as even children could buy and carry mugs of beer through the streets provided they were covered with the official 'Tamper free' seal.

John Green had been the Tenant of the 'Flu' for many years until he bought it during Lord Middleton's sale of local properties. After John Green's death there were a few tenants, the last George Creswick from 1889 until John's daughter Martha Fearney returned in 1891when it was passed to John's Grand- daughter Harriet Fearney, now Mrs. Thomas (Tom) Kirby, and it is the Kirby's who were the most associated with Totley village than all the other publicans. From the late 19th.c Totley Hall Lane farm was owned by Heald Unwin from Dore, whose son Fred built the semi- detached houses on the S.W. of Baslow Road above the Hill-foot junction about 1904, moving into the bottom one 'Fern Mount' after his marriage. Miss Harris, music teacher to my brother Elijah and myself lived in the next house until she moved to Main Avenue in 1926. Heald Unwin sold the farm to Arthur Fearney, brother of Harriet Kirby and went back to Dore, but Arthur was not a very good farmer and in 1923 he sold all the land behind the 'Flu', on which Stock's Green is now built, and as far as the rear of Totley Hall, to his sister Harriet thereby creating a new farm at the comer of Hall Lane and the Main Road that was managed by Arthur, Tom's younger son. Tom Kirby died around 1923 when Thomas, his elder son took over the Fleur de Lys, and Harriet, his Mother, left Totley for a time, returning about 1926 as Mrs. Cross, when she built and lived in the farmhouse on the comer of Hall Lane.

In 1929/30 Arthur Kirby married Catherine Parkinson, Grand- daughter of Thomas Andrews previously of Totley Hall Farm and later of Mooredge Farm, at the comer of Moorwood Lane, Holmesfield. The Crown Inn in Hillfoot Road, The Cricket Inn and The Grouse Inn in Totley Bents were all popular 'pubs' with there own special atmospheres, although, of course women did not enter 'Pubs' at that time, for it was the surest way to lose one's reputation! More about 'Pubs' later.

Washing day was a weekly occasion, done by hand with a Tosher', a 'Scrubbing board' and a 'Peggy-legs' by the housewife kneeling beside a large tub with corrugated sides that could be used for scrubbing larger articles, or work clothes that required an extra strong rub. Systems varied, some housewives sorted the clothes on Monday and put the 'Whites' to soak in cold water overnight, others did the washing on Monday without previous soaking, whilst others did the brushing of suits, emptying pockets, securing or stitching-on buttons where necessary, and re-hanging those items that weren't for washing this week. My Mother belonged to the last group, for a good reason, as, like many other wives, the drying-ground had to be shared. This was the day of large families compared with today, of cottons and woollens, blankets and unbleached sheets, frills and flounces, flannel shirts and starched collars, which all required clothes lines and hanging-out space more than the usual yard would permit, for there were no electric dryers. So, sharing and planning was the name of the game, share the yard, share the clotheslines, share out the days! You do yours on Monday, I'll do mine on Tuesday, and that's what my Mum and Mrs. Smith next door did. It had other benefits too. Try folding a heavy Whitney blanket, or four hill-sized unbleached cotton sheets, or even bleached if you were lucky enough to have them, on a good breezy washing day without one of the corners hitting the dust, and you would soon know how good it was when Mrs. Smith, or Mrs. Salt, as the case may be, came out to help. Two housewives standing facing each other, deftly gathering the ends of a sheet sides to middle, rocking back on their heels; pulling and stretching; folding and stretching twice, then one passing to the other for the final fold, all creases gone, no ironing needed, just put through the mangle and on the clothes-horse to air.

The same system, in various modifications were practiced in most households, organised days of baking so you could borrow a couple of loaf tins if necessary, shared mince pie tins at Christmas, and the inevitable 'Cup of sugar' when required. It all went with the ever-open door, the cheery call "How are you?" "We're going blackberrying, are you coming?" or, in the village those neighbours who went gathering firewood in Gillfield wood, returning with huge bundles strapped on their shoulders and laughing their way through the latest gossip.

Part Three

At our house washing-day started before breakfast when Mom disappeared down the stone steps into the cellar kitchen and lit the copper fire, filled the iron copper with cold water, and put the whites to soak in cold water in the peggy-tub. Breakfast over, kids gone to school, something prepared for their dinners at 12 o’clock (It's lunch these days!) and work began. The soaked sheets were put through the huge mangle rolls, and put back into the emptied tub, now filled with hot water from the copper, a pile of clothes on the flagged floor to kneel on and rubbing and squeezing began.

First were the white sheets for they took longer to boil and needed long drying-time, After rubbing where necessary the peggy-legs were brought into action, twisting one way, return and twist again, ponch down and twist again, it went on for minutes, until the sheets were deemed clean. Then the action that always mesmerised me when the ends of the sheet were grasped in both hands and twisted; grasped further down and twisted again; repeat until the whole sheet had been twisted and rung-out, as it gradually curved around Mum's arm up to her shoulder like a snake in an Arabian night's opera. The action was repeated for the rest of the sheets and the whites until, all done, the tub was emptied and filled again with water from the copper, and the procedure was repeated, the second time finished by a turn through the huge mangle rollers, and back into the now emptied tub filled with cold water for a good rinse. The final squeeze was through the rollers twice, tightening the cog-wheel a little for the second turn, and out into the yard to hang on the line by all four comers where it filled with wind like the sail of a racing yacht.

The same procedure was followed for all the wash in rotation; whites, coloureds, towels, work clothes, as deemed necessary. In between there was dinner to cook for the kids at 12 o'clock, usually something that could be put in the oven and checked from time to time as convenient. Plus a meal for Dad when he returned from the Pit about three o'clock after setting-on the afternoon shift at Strawberry Lee Pit. My favourite was oven bottom chips with fried egg, but the boys never seemed to mind, except Elijah who liked bread and butter pudding sometimes made with a left over teacake, whatever he had first.

Of course Shrove Tuesday was pancake day, when Mom made a huge yellow bowl of batter and stood at the fire-place making pancakes until we had all had enough, or until there was just enough to make one for Dad, because he would cry his eyes out if he didn't get a pancake on Shrove Tuesday.

There were two shops in Totley, one dating back into the 19th century still owned by Charles Thomas Jackson, known, and usually referred to as Choppy Jackson, or Shoppy by some people depending on the reason for the name. Shoppy referred to his occupation. Choppy to his habit of chopping a little off a bacon rasher when the scales went down too fast. Choppy had a strong sense of humour and was popular, but a 'Canny' sort of human being both as shopkeeper, and as baker. His bakery was in a separate building on the comer of Hall Lane and the narrow lane behind the shop leading to Grange Terrace.

As a young man Choppy organised his day so that he could take a late afternoon/evening siesta and start working in his bakery about ten p.m. to produce the first loaves by opening time. By mid-afternoon all baking was finished but the ovens were still hot, so housewives could take their loaves, already mixed, kneaded, and risen, and have them baked for 1d. per loaf, an arrangement fully appreciated by the housewives, particularly those in Hall Lane who took full advantage.

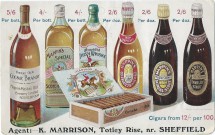

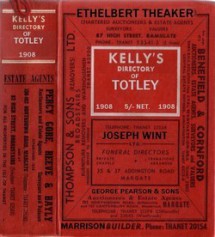

Walter Evans's shop in Hillfoot Road was previously an Ale House at one time run by John Fisher, and probably still had the licence for selling liquor, for I can remember seeing bottles on the shelves that could have been 'Pale Ale'. The shop was very different in the twenties, as the entrance at that time was down a path to a side door, passing by a large window that displayed all kinds of goods, some on stands, others on shelves at the sides and at the back. Everything but fresh meat could be obtained there, but, as at Marrison's at Totley Rise and other shops that sold groceries, most items were displayed in bulk, or in packages weighed out by the shop-keeper into bags of various types and sizes.

Sugar was sold in 1lb. and 21b. blue paper bags, with tops folded and sealed with glued paper from a large reel such as the one on the counter used for immediate sales. Preserving sugar, particularly during the summer jamming season, was often sold straight from the sack as required or, for busy times, weighed out into 3ib, bags for quick service. Flour and Grist, was sold ready weighed into large white paper bags weighing ¼ stone, ½ stone, or l stone (14 1bs or 6 ½K), similar to the Chandlers of today who still serve flour, grist, wheat etc straight from the sack. Biscuits were served straight from the large square tins on display on the counter or shelves, and many items such as ginger, pepper, cloves, and cinnamon were served from tall glass jars displayed on shelves, using a small scoop, and it wasn't unusual to be served sweets in a cone of paper deftly twisted into shape by the shopkeeper. Most sweets were 2d a quarter so the Saturday penny spending money could buy 2oz. of Blue Bird chocolate toffees, and the penny from Mom on Friday was a bonus. Prices between the wars seldom changed, a tin of salmon was always 3s 6d. and a loaf of bread 4 ½d, but then wages remained the same, unless awarded for extra responsibility, training, experience, or heavier workload, not annually as today.

There have been so many changes since the 20s and 30s that it is difficult not to become boring, "I've heard it all before" "Things have changed Mum" "Move on", but, though some changes have brought easier and more interesting lives and prosperity for so many people, memories don't move on. Imagine a bright moonlight night shedding light over the fields and moors, and somebody says "Let's play Holler", and all the kids at Lane Head, boys and girls, divide into two teams, the foxes and the dogs. The foxes set off down Lane Head Road, shouting and hollering as they race down to the Bents and up Moss Road, or Strawberry Lane, and spread out onto the moors. The dogs follow, hooting and calling "Shout Holler or the dogs won't toiler", and a Loud "Holler" comes back from the Bents, Strawberry Lea or high on the moors the Brickyard or Gillfield wood. The dogs keep shouting, the foxes keep hollering back. It could go on for hours, but the mums and dads never worried, they could hear where we were, and knew what we were doing, knowing that when the foxes were caught, or everybody had had enough, we would all return safely and go to bed without any prompting after a wonderful evening.

We played 'Peggy' when a short stick was placed on the top of a wall and in turn, using a long stick, would strike the 'Peggy' and watch it fly through the air and see who could send it farthest. No prizes, just honour!

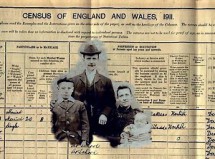

Part Four

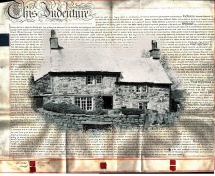

The recent changes in the centre of Totley village have completely transformed it from the one known throughout the years, it seems almost since Domesday, for the farmhouse on the corner of Hillfoot Road and the main road, opposite the market cross and entrance to Cross Scythes farm, had been the heart of the village since before the new turnpike road was created from Owler Bar to Sheffield in 1818. Summer Lane, possibly one of the new developments resulting from the more easily accessible village, had been known by various names, Ogden's Walk in 1880 after an important resident who lived here. New Row in 1891, when residents were diverse characters and occupations, some moving in from other parts of the village.

One such was Joseph Ward, stonemason, with his wife Ann, son Henry and daughter Eva. Henry, later known as Harry Ward, lived in what was then known as Chapel Walk, now referred to as Chapel Lane, in one of the houses overlooking the path. Perhaps there are some Totley residents who remember Harry's son Ernest, who married Doris Turner, daughter of Mr. Turner, one of the leaders at the Chapel, who lived in Lemont Road, Green Oak. Doris was a member of the Chapel choir and both she and Ernest were members of a local choir, the name of which eludes me, but should any of the Wrigglesworth family still live in or near Totley they may know, for, after Ernest's untimely death, Doris was for many years a member of the choir created by Dick? Wrigglesworth.

William Green, file cutter, who with his wife Elizabeth and children Amelia 11, Harry 8, Effie 5. Arnold 8, now lived in New Row and this Harry, I believe, was the friend of my Mother, who often spoke of his sister Effie. In the 20s Harry was the joiner and coffin-maker who lived on Glover Road at Totley Rise, and about 1930 was the last publican at the old Fleur-de-Lys in 1932, and first in the new one in 1933. There were so many file-cutters in Totley in the early 20th century, in Hall Lane, Lane Head, New Row, and Hillfoot Road, that one is led to think that they might have been out-workers for the forges in the valley, much as the 'Little-Mester' farmer in Cordwell, Elijah Green, who was a tortoise-shell penknife finisher for a cutlery firm in Sheffield. There may be records somewhere for anyone who has the interest and time to search.

Two elderly sisters, Olive and Alice Green lived in one of two cottages nos. l and 2 that still stand at the entrance to Summer Lane, next door to the Kenworthies, already mentioned in a previous article. Until his death, James Green their Father lived there with his wife Millicent, sons James and William, and Olive and Alice. Another daughter had married my Mother's Uncle, Henry Peat, a besom maker, son of John and Ann Peat of Piper Cottage opposite the top gate of Blackamoor. The records describe James Green as a carpenter, but my Mother often spoke of him as being a famous clock-maker, more correctly a clock cabinetmaker, his work apparently known for many miles around the district and Sheffield.

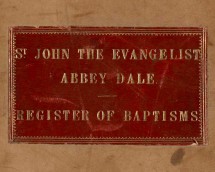

Those Totley residents who attended the Wesleyan Chapel in the 20s will remember Olive and Alice Green, for they were two stalwarts of the congregation, unique, prim, always walking with their rolled-up umbrellas, the backbone of the Chapel. James's son James was also a cabinet case maker, but William his youngest son may be better known to the older residents; He lived at the far end of Summer Lane and worked as a gardener at Totley Hall. He was a well-known character with a pronounced rolling gait that brought many humorous remarks from the lads. William was father of ? 'Cobby' the main butt for the ridicule of the Headmaster, John Wood's sarcasm, and Harold ‘Nobby’ whose wedding was the first to be held at the new Church on July 25th 1924. It was at his wedding that the custom of locking the gates first started when the lads of the village, as a prank, fastened the gates to the Church and made the bridegroom pay a fee of half a crown (2/6) to have them opened. This was supposed to be a 'One off, but became a habit and, in 1936 after my wedding, my new husband made sure he had a half-crown in his pocket to pay the toll.

The farmer at the comer of Hillfoot Road, more correctly the cow keeper was Joseph Wainwright, son of George Wainwright, Great-Great-Grandson of George Wainwright a Methodist Preacher and Weaver, who was born at Dons in 1717, whose portrait hangs in the Cutlers' Hall Sheffield. The Cutlers' Company had an ingenious way of raising funds to celebrate important occasions, as they did in 1809 to celebrate George III's Jubilee, by inviting a group of very notable citizens to dinner at the Cutlers' Hall who, in return for a donation to the Company's cause, received a self-portrait. The oldest guest was George Wainwright, whose portrait was painted by a Leeds artist by the unusual name of Schwanfelder. In 1926 the portrait was given to the Cutlers' company by a relative, W.G. Mitchell -Withers and still hangs in the Cutlers' Hall, Sheffield.

Joseph Wainwright had three children George, Harriet, and Sarah who, though very proud, were sadly not very bright, and none of them ever married. There was only a small amount of land and a cow shed close to the farmhouse so one assumes that the cattle were turned out during the summer to graze in local fields, as were those in the city farms in Sheffield. After Joseph's death in 1897 the shed and land were used for a few years by a local man and, though derelict, the shed was still there at least until the end of the war in 1945. By 1898 three cottages had been built on the land at right angles to the road at the end of the bank down to Summer Lane, whether by George, Joseph's son, or by sale of the land to a local builder is not known. The family stayed at the farm until 1900, when George and his sisters moved into the middle cottage in Baslow Road, where they remained for many years.

In 1909 Emma Fisher lived in the far cottage with three of her children, when she left Hallfield Farm after the death of her husband, Francis. As a child, Emma was one of the last pupils to attend the National School in Hall Lane, at a cost to her Father, George Hodkin, of one penny per week. After the Wainwrights left, the farm house was sold and became the first Post-Office in Totley, when my Great Uncle, Arthur Bradley and his wife Alice moved from Butts Hill cottages and Alice became the first Post-mistress. Arthur continued working at Totley Hall as Forester and acting Head- Gardener until 1904, when David Lewis, a newcomer to Totley, became the new Head-gardener with Arthur Bradley as Forester and Under Head-gardener. On the same day in 1904, Mr. Thomas and his wife, parents of Archie and Ernie Thomas, came to Totley to take up the post as the first Butler at Totley Hall.

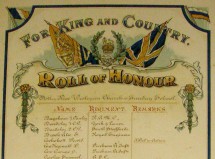

On the outbreak of World War I, both men were called-up for war service, in jobs that allowed Mr. Lewis to return to the Hall at certain times to keep his eye on the glasshouses, and Mr. Thomas was employed in special work in Electricity, and during their absence the duties of Butler were taken over by the Parlour maid. David Lewis returned to the Hall after the War and remained there until Mrs. Milner left in 1933. Mr Thomas continued to work in his wartime job in Sheffield and the post of Butler at Totley Hall ceased.

Archie Thomas was a fast runner, later to become a member of the Sheffield Harrier's Club, but when he was about 11 or 12 years old, he became a life-line for Alice Bradley for, although Totley could receive telegrams, they were unable to deliver them outside the village and, according to the Parish council minutes, there had developed a little animosity between her and the post- mistress at Totley Rise, over the delivery of telegrams. Archie stepped into the breach and started delivering telegrams from Totley Post Office destined for Holmesfield and Cordwell Valley, the only long distance deliveries from Totley, and this solved the problem of the postmistresses. Archie said he could run up the Park and down Millthorpe Lane to Carpenter's cottage in 2mins, but it took him a little longer to run back! By the twenties, Totley had it's own public telephone box that stood outside Choppy Jackson's shop, a boon for the residents

Another well-known resident of Summer Lane for three decades was Emily Green, daughter of William Green, a file cutter who had moved from Hall Lane to the house and shop beside the post-office. It was a two-level house, the living area reached by an outside flight of steps, where William lived for some years. The shop at ground level sold almost everything in the way of sweets, knick-knacks, dressmaking accessories, pens and pencils of all makes, in fact, if anything were needed, try Emily Green's first. However, Emily really was a dressmaker with clients for miles around, whose working rooms were also upstairs at me back of the house, whilst her niece Mabel, a demure little person, effusive in her smiles, helped to serve in the shop below. About 1930, Totley's first chip-shop was opened by Tom Kirby, son of the Fleur landlord, on the main road next to the old barn where fish and chips cost 3d, (2d for the fish and 1d for the chips); the fish being a thick slice from a huge Cod, not the fillets as sold today. It was a favourite meeting point on Friday and Saturday nights by the young folk, and sorely missed when it closed a few years later.

However, it was not long before Emily, a true business woman, opened a new chip shop in Chapel walk, next door to Harry Ward, which was reached by a flight of steps next to the Wesleyan Chapel. Although somewhat out of the way, it was very popular, and Mabel seemed to smile even more as she deftly served fish and chips. There were of course other means of obtaining the necessary things in life when Mr. Gillespie came round once a week with his covered dray, bursting with household goods such as pots and pans that hung from hooks around the sides of his dray, plates and dishes and fancy pottery, floor-cloths and dusters and almost everything necessary to the general cleaning of the house and, most important, paraffin for the lamps for, although Emily Green sold paraffin along with everything else useful in an emergency, it had to be carried home, whereas Mr. Gillespie brought it right up to the door, a boon for a busy housewife.

However there was stillroom for another delivery man nicknamed 'Pot-mold', real name Philip Coates. Pot-mold earned his name on account of his habit of shouting "pot-mold" all the way up the main road to announce his arrival. Pot-mold, a hard yellow natural stone that cost 1d per piece, was used for rubbing around the edges of steps where decoration was not the primary intention, whereas Donkey-stone, also sold by Pot-mold for 2d, a pre-formed block was used where a little decoration was called for, or a more refined look like the front door step. Of course, Pot-mold sold all other things one might need in the way of polishes for shoes, furniture, brushes, dusters, in fact, between them Mr. Gillespie and Pot-mold supplied everything one could possibly need for the running of a happy household, including the garden and toilets. For disposal of the worn-out, shrunken, and otherwise unwanted items there was the Rag and Bone man, who came round once a month with balloons flying in the wind from his dray full of cast-offs, throw- outs, shrunken jumpers and clothing too small for further hand- me-downs. However small the item begged by the children from Mum, in return was the gift of a balloon, a paper windmill or, if the goods warranted it, a penny.

Then there was the Trumpet man, a very refined and polite man, who had a large clubfoot and walked with a pronounced limp. We never knew his name, but he came round about once a month, when the weather permitted and stood in the middle of the road, playing songs and well- known tunes on his Trumpet. He obviously was a good musician, much appreciated by the residents at Lane Head, especially when he played one of their requests, and they were very generous with the money they put into his hand when he finished.

The opening of the new main road had allowed the village to expand and soon there was a new lane. Lane Head Road, that allowed access to and from Moneybrook and the Bents, without the necessity of walking along Penny Lane, up Chapel fields to the village to catch the Stagecoach and later Hatty's 'Bus to Sheffield, or out into Derbyshire. An early map of 1845 shows a building at the top of the lane, occupied by a fanner, Samuel White, and there was still a pile of hewn stone in the fenced-off area at the top of Butts field when we played there throughout (he twenties. By 1875 a cottage had been built on the opposite comer of the lane with a cow- house, a shed, and a file shop that was also occupied by a fanner, Samuel White, who could be the same man who wanted more buildings, or the first Samuel's son.

The remains of the cottage and buildings were still in the old farmyard throughout the twenties and thirties, when the shed was used by Billy Gascoigne, as a garage for the big traction engine that he drove for Pickford & Holland, and the farmyard gradually evolved into Gascoigne's garden. By 1875, three houses had been built at the top of Lane- Head Road, below the cottage and cow-house, one of which, in 1883, was the home of Edward Abraham Salt, my Grandfather, his wife Julia and their seven-month-old daughter Isabella.

Part Five

Ben Salt, Edward's brother lived next door with his wife and family. Both Brothers worked in their father Joseph Salt's clay mine on Totley Moor, (mentioned in an earlier article) which, about 1899, was sold by its latest owner, Mr. Batley, to Joseph Holland, to become part of Pickford and Holland's. In those early days, the Brickworks were open to the sky, when Jack Slack passed our door every evening just before dark, carrying his lantern and 'Snap-bag', knowing that he would probably have company through the night, for Tramps passed regularly up the road from the Workhouse at Sheffield on their way to the next Workhouse at Bakewell, and a warm night and the possibility of a mug of tea was not to be missed. The Kilns then were open to the sky, the light from the fires being visible for miles around and it was not unusual for a tramp to walk in and have a cup of Jack's tea and a warm seat for an hour. The outbreak of World War II changed many things, especially the Blackout, and very soon a roof was built over the whole Brickyard site in order to blot out the light from German planes.

We do not see tramps these days, but before WWII they called at our cottage regularly, on their way from the workhouse in Sheffield to the next one in Bakewell, asking for a pot of tea and a bite to eat, and my brothers and I swore that there was a mark on our gate telling all the tramps and gipsies that we were a soft touch. But, as my father explained, they were respectable men who were either looking for work or they preferred that way of life. He also explained that, according to the Vagrancy Act, anybody could be apprehended in the street by the Police, if they suspected that a person had no means of paying for a night's lodging; if not they were taken to the nearest Police station for the night as a vagrant.

The Workhouse system avoided such disgrace by giving the man supper, a night's lodging, and breakfast, in return for some simple work, and next morning giving him a sandwich, and a shilling, to offer to another workhouse for his next night's lodging, thus avoiding arrest as a vagrant. It now seems a strange law, that asking at someone's door was different from begging in the street, for under The Beggar's Law, the police could arrest anybody and take them to court for the latter, but not for doing the same thing at someone's door, because, I presume, he had money to pay if asked, and of course, he never was. Such are the finer points of the Law.

A few years ago I asked a policeman friend if these two laws had ever been rescinded, and he said that he had never heard of them, but would find out. He contacted me a few weeks later with the news that no one else in the office had heard of them; but had investigated and, yes there had been such laws, and they had never been rescinded, just faded away through not being used! Father said we were never to turn away a Tramp and my Mother said the same about gypsies who called regularly, selling lace in the early 20th century.

Part Six

The Bents was a thriving community of seven farms, two in Moss Road, one at Moneybrook, another at Moneybrook Rise, two in the Bents, and another across the fields at Old Hay. The Hamlet of Old Hay had been a thriving community in the 19c, with its forges, mills, and John Dalton's Paper Mill, but throughout the twenties and thirties, it was the playground in winter for Totley residents of all ages, who skated on the frozen Dam. The experts like Charlie Coates taught those who couldn't skate, and the young ones used the icy surface for making perfect slides, and all ages had a wonderful time. Sadly the dam was filled in years later, after a local man had used it to commit suicide.

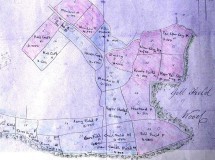

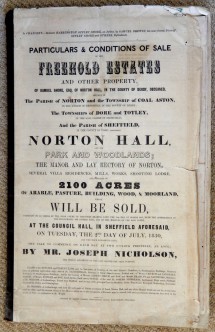

About 1885, a cottage and two small three-story houses were built into the hillside on the main road at Lane Head, on allotment land that was under the Jurisdiction of Rev J.T F. Aldred, Vicar of Dore, and in 1889 a plot of land 1222 sq. yds. with a frontage on to the main road, containing four houses, three newly built, and a cottage, was sold at auction by Auctioneers in High Street and Castle Hill, and Solicitors 'Burdekin, Benson, and Burdekin' of Norfolk Street, Sheffield.

At the time of the sale, two of the new houses were occupied by Messrs. Handley and Coates, and by 1891, James Green, File Cutter, had moved into the third one with his wife Ann and their children. Sampson age 22, also a File Cutter, Tom 14, Jessie 9, Steven 3. James, a later son was also to become a file cutter, who still lived in the same house with his wife and son Harold during the 20s and 30s. Jim Green's hobby was breeding canaries, a hobby that made him famous for miles around. As children and playmates of his son Harold, he occasionally allowed us to enter his cellar and look aghast at the beautiful birds in the cages that lined the walls, all different in colour, shape, and song, due no doubt to Jim's clever interbreeding.

In 1891 Edward Dalton of Lower Bents Farm, descendent of the Daltons, Yeomen farmers of Lower Bents farm and Overseers of the Poor for two centuries, died, and his wife, nee Elizabeth Peat, my great, great Aunt, moved into the first cottage at Lane Head, and Albert Fox and his family moved into Lower Bents Farm. Kate, one of Albert's daughters, married Joe Burgess, a local man, and for many years Rose Burgess his daughter lived there with her husband, Bill Taylor, until her death.

I was born in the Old School House in Hall Lane in 1915, leaving there with my parents and 3 year old brother Elijah in 1916, for our new home in the same cottage at Lane Head that was to be my home until I married a Sheffield Policeman in 1936. Residency was stable at Lane-head for a number of years after 1916, until the Putrells, our next door neighbours, left in 1925, and the Ramsells joined the small community at Lane Head.

The top house was the home of William Gascoigne, who drove the big traction engine for Pickford and Holland. Maurice Jobnson with his wife and five sons resided in the second, James Green in the third, with Arthur Ward, his wife, son Arthur, and daughter Bertha, the long-standing residents of the other cottage in the middle of the row. The Ramsells were next on the opposite side of the steps down to the back yard, whilst the Smiths were well established next door to us, the Salts in the bottom cottage. This situation lasted for thirteen happy years, during which time I had left to be married, until 1938 when the Smiths moved out and became the new residents in the Old School House in Hall Lane, now enlarged inside by putting in a new floor/ceiling to create more bedroom space than the original building.

Soon there were new residents at Lane Head after the cottage and the two bottom houses were sold and the daughter of the new owner moved in. After many years of negotiating between my Father and the new owner, he finally moved to Moorwood Lane in 1947 and there have been many changes since then. The rest is modern history!

A year after John Wood became Headmaster of the Totley Church of England School he, and the Headmaster of Dore School, organised a Pageant to commemorate the anniversary of the meeting between King Eanred of Northumbria and Ecgbert, King of Wessex in 829; whose symbolic Wyvern is displayed on a Stone on the village green at Dore. When Ecgbert finally conquered Mercia, he continued north, following the boundary between Mercia and Northumbria.crossing the Mytham bridge at Hathersage, following the boundary between Mercia and Northumbria, over Big Moor, finally reaching the ridge over Totley Moor to Dore. However there was no battle, for Eanred surrendered to Ecgbert, who now became the first Overlord of all England and was crowned King at Winchester, the Capital, a month later. Sad to say, his triumph did. not last long, owing to the Danes, but that does not detract from the fact that Ecgbert was the first King of England. According to the account told to me by our neighbour, Arthur Ward, when I was a very young girl who hardly understood the implications of what he was saying, without describing the actual formation of the soldiers, explained that the positions of the respective armies were reversed at the pageant, when Ecgbert's army of Mercians on the ridge at Dore, were Totley pupils, whilst Eanred's soldiers of Northumbria in a field at Avenue farm were pupils of Dore school. This might have been symbolic in the fact that no actual battle took place. Who knows?

Perhaps the most memorable event in our teenage lives was the advent of the Talkies. Not that Totley residents made a habit of 'going to the pictures', for the nearest Picture-house was six miles away at Abbeydale, near Broadfield Road. The cost of a seat in the stalls was 9d, which is just about the same as today .considering that no man in the twenties earned more than two pounds a week, and most were nearer one pound. Youths were lucky if they earned fifteen shillings a week, which was handed over to Mother for housekeeping (Father in our house), in exchange for spending money.

I was eight years old when my Father took me, my brother Elijah, and Nellie Smith from the house next door, to Abbeydale Picture House to see one of the classic silent films, Charlie Chaplin in 'The Gold Rush'. It was impressive, especially when Charlie's hut was blown away in a gale and he was left at the top of a precipice, eating his boots. A year or two later, when the Talkies 'The Singing Fool' and 'Showboat' came to the cinemas the effect was even more impressive when we actually saw the kneeling Al Jolson with pleading arms raised to Heaven, singing 'Sonny Boy', Such was the interest in this new phenomenon, that soon there was a cult of filmstar worship, sometimes heart-throbs or strictly as actors.

Even my father soon had his favourite actor, Alistair Sim, whose cryptic sense of humour never failed to tempt him into Abbeydale Picture House, and soon the faces of famous Stars replaced those of footballers and animals on cigarette cards.

Part Seven

In 1948 the new Health Service came into force and at the time it was applauded as a means of free treatment and medicines for all and, had it not been treated as a free handout for every minor ailment, it might have weathered the advances in medical technology and increased costs of treatment and fulfilled the dreams of Beveridge, Churchill and the Government. From the moment that the N.H.S. was created many doctor's surgeries and outpatient departments were inundated with requests for simple things like aspirins, plasters, and treatment for the smallest cuts or minor wounds that hitherto had been treated at home.

Very soon it was evident that some restrictions should have been included, and the purpose of the N.H.S. more clearly defined as being for more serious illness and hospital treatment. Some members of the community wondered why the new system was so essential when, until the end of W.W.2. no-one in the village had been denied treatment when necessary. Totley was not alone in such thinking because as part of the existing Voluntary Hospitals System most villages, and areas of towns and cities had their own Hospital committees. Friendly Societies and other organisations dealt with emergencies and since W.W. 1 it had been considered a pleasant duty to work for the hospitals, even the children played their part.

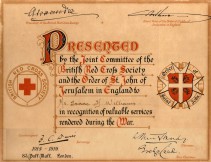

During the war Mrs Colin Thompson, wife of the Totley Rise butcher and her daughter along with Nellie Gill, Sister of ‘Choppy’ Jackson, and other local women had been nurses at the war-time Hospital for injured soldiers in St. John's Church Hall Abbeydale (More later), and both ladies were also members of the Totley Hospital Committee. My Father and Mother (the former also representing the Parish Council), were both Committee members with Mrs. Milner of Totley Hall their Chairman. As a School Govemer Mrs. Milner was well acquainted with some of the problems of the children and their parents and once a year the ladies of the committee were invited to the Hall for a very informal afternoon tea when the welfare of the village was the main topic of conversation.. As with all committees each member had his/her special responsibility and my Mother's was to collect the hospital contributions from all working men. Many years later she told me that no man paid more than 2d a week, for the average wage was about £l-10s (£l-50p), very few reaching the princely sum of £2; some of them also subscribing the same amount to Dore Friendly Society in case of future need.

In Totley, whether through illness or death of a husband, we had the occasional call by a lady from the village asking to see my Father as representative of the Parish Council for his help in obtaining the 'Parish' i.e. the amount paid to a widow on the death of her husband, or, in case of illness, the amount allowed for children. On such occasions we children were instructed to "Take the lady into the room" and ask no questions. (the 'Room' was the sitting-room or parlour at our house) The amount of the 'Parish' allowance was 2s 6d (12.5p), with additions for each child, not a lot today but in the 20s and 30s it could have been an eighth of a labourer's wages.

However, the hospitals did not have to rely on subscriptions because the committees were constantly working at some project to make money, by whist-drives, usually in the school and, after the Labour Hall was built, an annual dance when all the refreshments were given by the public. The greatest effort, however, was the work put in by everybody during the annual food collections organised by the Committee to supplement that provided by the hospitals themselves.

Many houses kept a few hens if they had either a back-yard or an adjacent piece of land large enough to house a small shed and, during April the main egg-laying season, the older children, often accompanied by younger brothers and sisters, went round the village with baskets of all shapes and sizes collecting contributions of eggs for the hospitals to lay down in large pickling-jars of Isinglass to be used for cooking throughout the year. Contributions could be one egg, possibly two or three, but occasionally a whole half dozen would bring a broad smile from the collector. Of course the greatest contribution was from the large houses and farmers, in which case the responsibility fell on the adults; anyone who owned any mode of transport, bike, motor-bike, or car, covering the distant farms, the 'Shank's pony' (Legs) collectors joining in groups and calling on those nearer to the village.

The committee were responsible for delivering them daily to The Royal Hospital Sheffield throughout April and the 'Pickling pots' were soon full for another year. This was followed by a similar collection of jam-jars ready for the fruit season starting with raspberries, strawberries, through to plums, damsons, and apples. Collecting continued throughout the long school holidays, but most of this crop was donated from the larger houses (Grove House, Totley Hall, The Grange), with smaller donations from small gardeners according to the sizes of their crops.

Of course with all these pickled eggs, bottled fruit, jams and jellies one might criticise the patient's diet, but every basket of eggs or plums meant that more money could be made available for other items that constituted a healthy diet and, if a patient fancied something different like an occasional fresh boiled egg, it could be brought in by a visitor and deposited in his/her locker. When the patient fancied a boiled egg, his/her name was written on it before boiling and it was served up just like at home.

This system continued for the first years of the N.H.S at least up to 1954, when one visitor brought in a few shrimps and it was found essential not to wait too long before having them served for tea in case the other patients rose in protest at the aroma coming from the locker! There has been much criticism of food in the old hospitals, rice pudding in particular, but, with experience of today's food the old variety of rice pudding was far superior to that of to-day, and those who have experienced modern hospital food I fear would not award a very high mark for quality.

Possibly the most important contribution to the hospitals was the voluntary service of the Doctors and particularly the Surgeons. There were two Doctors serving Totley. Dr. Parsons, who was also the school Doctor visited the school at the beginning of every term to examine the new intake of pupils, and attended most children at home when necessary. Dr. Marshall, a Doctor, and also a Surgeon, attended the Royal Hospital on Tuesday each week as a volunteer for work in the Theatre. Dr. Parsons standing-in for emergencies in the village. Neither Doctor had an appointments system; if a visit were deemed necessary, you just went and waited your turn to be seen. Dr. Marshall's surgery was more like a small hospital as Mrs. Marshall was a pharmacist and all medicines prescribed by the Doctor were dispensed by her immediately; any other items like ointments, plasters, and readymade lotions being handed out by the doctor himself.

Over the years the cost of treatment by the Doctor has often been criticised and mis-understood, for the Father's contribution covered his children as well as himself, and treatment for his wife, either surgery or hospital, was subject to a means-test, and the assessments were very generous. In 1934 an eighteen year-old village girl had to have long-term hospital treatment for gland infection and during her first visit the Almoner (income assessor) asked about her father's occupation. He happened to be a well-known business man who was asked to attend the Almoner's office in order to assess his financial situation. Interview over, assessment complete, and he had nothing to pay; the long-term treatment was necessary and free.

All children looked on these summer activities as another game, what's more, an adult game in which they could take part and feel 'Grown-up', for although there always seemed to be plenty to occupy the adults there was little for the very young at Lane Head, particularly for the two youngest girls, myself and the girl next door who was not always well enough to play outside, and I was often quite alone. My Father would not allow me to play in the village or in the Bents, the two places where I could find those of my age; he liked to know exactly where I was and what I was doing.

Luckily my Mother had a wonderful capacity for inventing games, usually one in the form of house-work. Friday morning was always the time of day when she black-leaded the big Yorkshire range in the living-room and, seeing her 4yr.old daughter 'moping around' one Friday morning, obviously without a playmate, she suggested we play a game of 'Black-leading'; I would do the basket fire-place in the 'Room' whilst she did the one in the kitchen, "And", she said, " let's see who can get the brightest shine". From her basket of brushes an old shaving-brush of my Dad's was produced, then a larger, nicely curved one with a handle to hold whilst polishing and a small piece of velvet for the final shine. Finally a small tin lid was retrieved from the bottom of the basket in which she mixed some Zebo powder to a paste with a little water. With one of her aprons tied firmly around my middle I was in business. Brushing on the Zebo with Dad's old brush was easy, though it was a good job that Mum had thought to cover the floor and hearth with lots of newspapers. The polishing was exhilarating; brushing this way; brushing that way; into the nicks in the carved design, not getting any into the tiles on both sides of the fire basket, with an occasional run to the kitchen door to see whether the Yorkshire range had a brighter shine than mine, then back again to give a final rub with the piece of velvet, all ready for Mum's verdict. ‘Oh my, oh my’ was the cry as she entered the room, and my chest was puffed out like a pigeon's when she added, ‘well we can see who's won this game can't we?’ There never was an outside game that came anywhere near the satisfaction of that morning.

It was around this time that I became acquainted with other kinds of houses quite different from our little cottage with its stone-flagged floor that Mom scrubbed and swilled every Saturday morning, for there were two ladies who lived in a big house in Victoria Road (later Queen Victoria Road), with bay windows much more impressive than our little casements. They were the Misses Dawson, two very elegant ladies whom I had seen sometimes at Chapel, who may have been responsible for the Mothers’ meetings held there, but I knew them as the ladies who held a monthly sewing-meeting that mothers with pre-school children could attend.

Dressmaking had been my Mother's favourite occupation since her schooldays so this was an opportunity she couldn't miss. I eagerly looked forward to the sewing meeting days to play outside in summer with boys and girls, not only from Totley but also from Bradway, Green-oak, Totley Rise and the Chemical yard. After about an hour cups of tea and small buns were served to the sewing ladies and the children were allowed a small glass of lemonade and a biscuit, but the really wonderful experience for me was walking on the lovely deep carpet that covered the floor, not like the ‘Clippy’ rugs that covered our stone flags. It was the first time that I had seen a whole floor covered with such luxury and I wanted to roll in it, to bury my face in it, and never to leave this house again. But, of course, it was only dreaming, and after two hours it was time for home and the ‘Clippy’ rugs, happy and already looking forward to the next time. ‘Clippy’ rugs, for those who are not familiar with the term are those made from the good parts of cast-off clothing, old skirts, jackets, trousers, anything that could be cut into 6" lengths, which, using a special ‘Clippy’ tool could be attached to a piece of hessian, a washed sugar or flour sack, or other piece of hessian that could stand the hard wear of hobnailed boots and countless comings and goings of many feet.

There were of course different ways of making rugs, some of them peculiar to the area, as the ‘Proddy’ rugs of Northumberland and Durham that are still made on special frames that in some houses are still kept in the corner of the room ready for making a new rug next winter. I was initiated into making ‘Proddy’ rugs in the 30s when I visited my new in-laws in County Durham and found them very easy to make, the frames taking the weight of the hessian backing. ‘Knotty’ rugs are those made with ‘Thrums’, the short lengths of special wool, such as the ‘Readicut’ variety that were made draped over the knees as were the ‘Clippys’, but each type needed it's own type of needle. The ‘Clippy’ needle looked rather like a weapon with its sharp pointed nose for cutting through serge, alpaca, and other heavy cloths, with a lever worked by the thumb to open jaws in which to insert the piece of cloth and pull it through the hole. No knots were needed for the rows were set close together, each one securing the last.

‘Proddy’ rugs are also made on hessian with balls of rug wool or long lengths of fabric approx. ½" wide either old or new and, in the case of wool can be individually designed and even reversed. This is not so with those made with cloth, for, although some form of design can be achieved by use of colour, there are bound to be ends of cloth on the reverse side due to using varying lengths. The needle used for the ‘Proddy’ rug is hollow with the end of the ball of wool or cloth passing through it from the top to the point at which it enters the hessian. As the point of the needle enters the hessian the end of the wool is held underneath by the other hand whilst the needle is pulled up again and inserted about ½" away thereby holding it in place and producing a stitch on both front and back.

Most people will be familiar with the ‘Readicut’ rugs that are made in a similar way to the ‘Clippys’, but the needle is not pointed because they are made on canvas, not hessian, and the ‘Thrum’ is grasped in the centre thus forming a loop through which the two ends are pulled thereby forming a knot. If that was boring then, for fear of becoming even more boring the following will be the last of the stories of the young folk in Totley early in the 20thC, for life today bares no resemblance to that of yesteryear. However, should anyone be around who remembers those halcyon days they will know who I am talking about when I mention Annie Nutty.

Part Eight

According to my Mother I had slippery feet for I was always asking to visit somebody, perhaps Mrs Coates who lived around the corner in Lane Head Road, or Mrs Siddall and the children at Strawberry Lea Farm their moorland home in the field near Blacka Moor. Mrs Siddall's husband Thomas was the Gamekeeper and Warden of that area of the moorland and, as an old neighbour of the Fisher family at Hallfield farm, was no stranger to my Mother when we moved to Lane Head.

Thomas and Florence Siddall lived in one of the cottages near the spring at the end of the short track opposite Moneybrook farm. We were at the end of the water pipe-line at Lane Head and had become used to the supply running out for one reason or another, and it wasn't unusual for the first one home from school at dinner time to be handed the big jug from my Mother's dressing-table and told to run down to the spring and fetch water for dinner-time drinks. I must confess that when it was my turn there was as much water spilt on the way back as there remained in that heavy jug by the time I arrived home.

Before we were old enough my Mother had done this and over the years the two mothers had become good friends and when the Siddalls moved to Strawberry Lea Farm it became a ritual once a year during the school holidays to pack a carpet bag full of 'Goodies' and set off early in the morning down Lane Head Road, up Moss Lane that led to the moor and the steep mountain path. Then came a short stretch where a little care was needed to avoid the nests of snakes on each side of the path in case one was the resting place of a poisonous adder. The last stretch around the mountain took us to the little latch gate that led into the huge expanse of open field where we could see and, after negotiating about 500yds of grass, pass through the gate in the high wall that surrounded the farm and into another world. Huge leaves of rhubarb filled an area as large as two allotments and quite obscured the potatoes, cabbages and other vegetables that grew on both sides of the garden path leading to the farmhouse door.

The routine was always the same: after unpacking the Carpet bag, and everybody having feasted on its contents , the boys went out to play with their new-found friends and I stayed inside absorbed in the quaintness of the farm house and the two great jars of fermenting 'Bumble-bee' wine on the high mantle shelf in which the 'Bees' floated up and down, around and around in a mesmerising rhythm whilst turning honey and sugar into wine. On the floor beside the fire was a large wooden cradle just like the small one my Father had made for me out of an ammunition box in which to rock the rag and china doll that Florence Savage had given to me on my first birthday. Its high sides and flat- topped hood kept the baby inside warm and cosy and to keep company with the constant conversation between the two mothers, Mrs. Siddall's leg fuelled the huge wooden rockers as the cradle rocked from side to side in a constant rhythm to match the 'bees' and to soothe gently off to sleep the latest addition to the family, a baby girl called Muriel with the most beautiful titian hair I have ever seen. After a few years, possibly when the moors were sold, our visits came to an end when the Siddalls moved into the Chemical Yard off Victoria Road.

There were other friends of my Mother to whom we occasionally paid visits but the one whom I most liked to visit was Mrs. Marshall who lived in the bottom cottage in Hall Lane. Mrs. Marshall had a son called Dennis, a few weeks older than myself, and I often heard the two Mothers reminiscing about the days when Dennis and I took our morning bath together when we lived opposite to them in the Old School House, or when both babes were held in our respective Mother's arms near farmer Unwin's well-yard whilst watching the huge horse that the farm lad tethered to a pole over the well every morning and left for the rest of the day to walk round and round drawing water for the farm. I loved Mrs Marshall almost as much as my own Mother and visiting her was a delight, but another reason why I loved to visit Hall Lane was a chance to play with my friends again.

Phyllis Ward, daughter of Fred and May Ward, who lived in the cottage set back in the garden near the old well was a few months older than myself and just beginning to talk when I was born. It was Phyllis who gave me my 'Nick-name', Dene, by which I was known throughout my school-days and youth because she could not yet say Josephine, And there was Gladys, one of the Cartwright sisters next door to Toft House, who years later gave me the idea of working at Totley Hall. All three remained friends throughout our schooldays even into marriage, but pre-school days were the memorable ones when we all played in the lane below the Hall gates where there was a huge oak tree growing high on the bank, its bare roots forming a roof over the lane under which farm carts and drays could pass.

How old the tree was no one could say, but Mrs Stubbs, Mrs Ward, Mothers, Grand-mothers, and even Great-Grand- Mothers since the 18c. knew Annie Nutty's tree and had played the same game. There was a ritual; little legs climbing up the bank and sitting there whilst knocking on the huge old black root and calling "Are you there Annie Nutty?", and if there was no answer the knock and question would be repeated until, if we were very quiet, the answer came, faintly but clear, "Yes".. Then came the next question, "Are you alright Annie Nutty?" the same question that had been asked for centuries, and when the answer came again " Yes", all would be well, for everybody knew that if Annie Nutty was alright then so was everybody else.

Now, you might say that this was only a child's game, but many, many years later whilst visiting my youngest brother Jeff,. in his restaurant in the old village of Whalley near The Trough of Bowland, I saw in all the surrounding shops black hooded witches hanging from shelves, or flying through the air on broomsticks, and Jeff told me that these were the Pendle Witches. Everybody in the area knew the Pendle Witches, some of whom had been drowned in the village pond as a punishment for their evil ways, but no-body knew what had happened to the most well known, Annie Nutty, who seemed to have escaped in the 1700s and was never seen again. I wonder what happened to Annie Nutty when her new home for the last 200 years, the old oak-tree, was removed to make way for the building of a College that G.H.B. Ward, looking down on it from Moorwood Lane in the 50s, described as a "Huge packing-case"

Inevitably little girls grow up and during the years at school there was little time for playing as they were kept occupied at home either dish-washing, ironing with the heavy flat-irons heated in front of a red-hot fire, or helping Mother with the cooking, especially in the larger families. Most boys aged 12 had morning, evening, Saturday or Sunday morning jobs delivering papers, meat or fish, either to earn spending money or to supplement Mum's housekeeping, whilst others delivered milk and did odd jobs in the evenings and weekends for farmers in the village and surrounding district, maybe singling turnips/Swedes in summer, chopping them for animal 'Fodder' in winter, or mucking out the stables and grooming the huge Shire and Ayrshire horses after a good day's ploughing.

On leaving school there was still farming for those who chose to have an out-door life, others could usually find jobs on building sites, either as bricklayers or joiners, labourers, or as tea-makers, until something else turned up, for Totley was expanding and local builders were taking advantage of the demand for houses.

Part Nine

The highlight of the year for both children and parents was the Totley Show that was organised by the Parish Council during the long school holidays in August with help from members from various organisations and judges for all the craft sections. There was something of interest to everybody of all ages and talents, and those who only came to watch and have a good day out were never disappointed. Activities began a week before the date of the show when lorry loads of stakes, ropes, trestle-tables, chairs and other curious pieces of equipment began to arrive in Earnshaw's field opposite Totley Grange with its picturesque setting framed by the huge horse chestnut trees in the avenue.

One piece of equipment of vital importance was the huge white sheet to be suspended at all four corners on suitable posts just inside the entrance gate at the bottom of the field, opposite Grange Lodge, (Now demolished). This was, of course, before Hassalls built the houses in the corner of the field. There was no avoiding the sheet for it almost filled the gateway and shouted out for pennies or any other donations to be tossed in and, although this was an unusual way of asking for an entrance fee, it obviously worked for by the time the show closed the sheet was almost full and sagging under the weight.

However, the really interesting money-spinner was the penny-trail that was strategically started off early in the afternoon by one of the organisers, who carefully placed a few overlapping pennies on the curb stones as an enticement for others to follow. The `Penny trail' was probably the most popular item on the agenda as more visitors left the field having made sure that they had a few pennies in their pockets and as they very carefully placed them on the curb stones the trail gradually grew longer, and longer, and longer. You might ask "At this moment in time?," to use a modern expression, "How did they stop the kids pinching the pennies on such a long stretch without any obvious supervision?"

The answer is, I am sure, not that they were more angelic or well-behaved in those days than the kids are today, although when their parents were around they knew that they might earn a cuff behind the ear if they dared even think about it; but they were interested, and hoping just as everybody else was hoping for that trail of pennies to reach Choppy Jackson's shop and an even bigger hope that it would turn the corner to continue down Hall Lane and break the record. It takes just a small thing sometimes to get everybody into the same mood doesn't it? Now back to the Show.

There were of course races of every kind, running for toddlers, Mums, Dads, and children in all age groups; egg and spoon, skipping, three-legged, sack, and wheelbarrow races for those who liked something more venturous and didn't mind being laughed at when things went a bit awry; it wasn't easy to stop the egg from wobbling without sticking your tongue out a `mile'; making sure your feet did what your brain told them to when skipping, you can't please everybody all the time!

Totley show, however, was not for sports alone, it was really for the results of a year's work for gardeners, artists, craftsmen and women; to show how they had cheated the weather, had coped with all the hazards and handicaps of home and work, in spite of which they had produced an abundance of food, flowers, plants, fine works of art in all media from pencils, pens, pastels and paint, through wood, glass and pottery, and that most important ingredient of life food, food in all its shapes and sizes, in pies, scones, cakes, biscuits, sweets and tit-bits; plants that are every showman's pride and joy, and flowers. It wouldn't be a show without flowers, those things that appear to provide nothing for food, unless by chance you like fried marrow flowers, but do something that no other commodity has the power to do, to raise the spirits and appreciate beauty and the aesthetic sense and science of the beautiful.

All these things were represented at Totley Show, many by the school children from the earliest age when egg-cups and jam jars displayed bouquets of wild flowers, older girls and mums showing their prowess at flower arranging for table, sideboard, or any other place the show committee could think of. Of course, picking wild flowers today would be frowned upon, and many species are forbidden, but in those far off days wild flowers were abundant; cowslips, violets, primroses, moonpennies (Matricaria maritima), field scabious and poppies, bluebells and wood anemones, and that bright yellow flower that little girls held under the chin to see if they liked butter, the Meadow buttercup, about which, it was said "If a few buttercups were hung round the neck in a bag they were thought to cure lunacy" food for thought!. A host of others filled the hedgerows, woodlands and pastures, which we were allowed to gather and the privilege was not abused.

When we were very young my next-door friend Louie Smith and I played in the butts field at the top of Lane Head Road where we sat contentedly in summer making daisy-chains, or gathering a few Milk-maids (Cardamine pratensis) from the little stream that came down from the brickyard, and under the road near the first Butt. A few violets might be found in the shade of the wall at the top of the field, eagerly handed over to our mums who accepted them with profuse thanks before arranging them in egg-cups to be proudly displayed on the window-sill.

Older girls and Mums showed their prowess at the show in the flower arranging classes, and there were many to choose from, for table, sideboard, or any place the organisers could think of, and young boys and girls showed the results of their own efforts in miniature gardens, on plates, in dishes, or any other container that Mum could spare for a day.

The older boys, however, were much more ambitious, and proud to show their expertise in woodwork through book-ends, trinket boxes, picture frames, and cricket bats, or occasionally more ambitious items, all produced under the eagle-eye and unstinting patience and guidance of John Wood, the Headmaster of the Church School. He it was who also tutored them through their drawing sessions following on from their earliest efforts with Miss Emma Marsden their first teacher as infants, who planted an artistic streak in many of her young pupils, and gave them a hobby for life. Drawing was my brother Elijah's forte, especially in his portrayal of animals, and every year at least one coveted 1st prize card would appear beside a skilfully- crafted, lifelike illustration of a 'Doe with Fawn', or a `Stag at bay' that could have put Landseer to shame.

As with any public event, whether for entertainment or otherwise, there had to be the usual refreshment marquee for the occasional cup of tea to keep the crowd happy and encourage a few more pennies to appear from their pockets for the day's good cause. However, the two major events of the show came towards the end, although one had started much earlier when the competitors of the Steeple Chase on the firing of the gun had circled the field then set off down the main road and Main Avenue to the field and the gap in the hedge to Joseph Salt's field on the edge of the brook where they crossed the wooden bridge and struggled up the field to Woodthorpe Hall, then the home of Mr. Wing a dog breeder. The dogs were kept in the open behind a 12ft. high fence surrounding the Hall and soon their barking could be heard down the valley indicating that the first of the steeple- chasers had reached the farthest point and were now on their way down Wing's field, across the wooden bridge over the brook in Gillfield wood on their way across the fields to Hall Lane.

Very soon the cheers of the crowd lining the lane when the foremost of the runners were seen could be heard on the show-ground, which was the signal to everybody to move towards the gate and form a tunnel of cheering clapping onlookers shouting the names of their favourites, and encouraging those at the back to "Go on, go on, get a move on". Then, as at the end of all long races, came the final run around the boundary of the field where the race could be either won or lost in the final sprint amid cheers, or tears dependent on whom you might have set your hopes on.

The last item on the Show programme couldn't be anything but the Tug-of-War the pride of the village, twelve proud men trained by Bobby Bagshawe, successful in competitions against the teams of Dore, Holmesfield, Dronfield- Woodhouse and other Derbyshire village teams. But none quite so important as the final on their home ground. My Father was a member of the team who one year could have put the `Cat amongst the pigeons' quite unintentionally, when after running in the chase, he collapsed on the field, for a reason still unknown, but serious enough for him to be taken to the medical tent and treated by the ambulance team where he remained for over an hour. Fortunately he suffered no lasting harm and was able to take his position on the rope, and the 'Pull' carried on without further mishap.

Sadly the Totley Show as it had been known for many years had to come to an end around 1925 due, it is thought, to the death of Mrs, Earnshaw and the sale of Totley Grange, The sports now became the School Sports organised by the headmaster John Wood and transferred to the Sic. (the cricket field in the Bents,) and they were still as popular for the children and parents although many said how they missed the excitement of the old Totley Show, even though one race, the steeple- chase did have a second lease of life when the oldest boys took to their heels and raced for their lives around the boundary of the field, ending through a tunnel of supporters shouting as loudly as they had ever done for the men.